Marcel Duchamp didn’t sign his name on a urinal for lack of ability to create “real” art. In fact, as explained by gallerist-Youtuber James Payne in the new Great Art Explained video above, Duchamp’s grandfather was an artist, as were three of his siblings; he himself attained impressive technical proficiency in painting by his teen years. In 1912, when he was in his mid-twenties, he could transcend convention thoroughly enough to bewilder and even enrage the public by painting Nude Descending a Staircase, which also drew criticisms from his fellow Cubists for being “too Futurist.” From then on, his independent (and not entirely un-mischievous) streak became his entire way of life and art.

That same year, Duchamp, Constantin Brâncuși, and Ferdinand Léger went to the Paris Aviation Salon. Beholding a propeller, Duchamp declared painting “washed up”; what artist could outdo the apparent perfection of the form before him? Getting a job as a librarian, he indulged in a stretch of reading about mathematics and physics.

This got him thinking of the power of chance, one of the forces that moved him to put a bicycle wheel in his studio and spin it around whenever the spirit moved him. This he would later consider his first “readymade” piece, deliberately chosen for being “a functional, everyday item with a total absence of good or bad taste” that “defied the notion that art must be beautiful.”

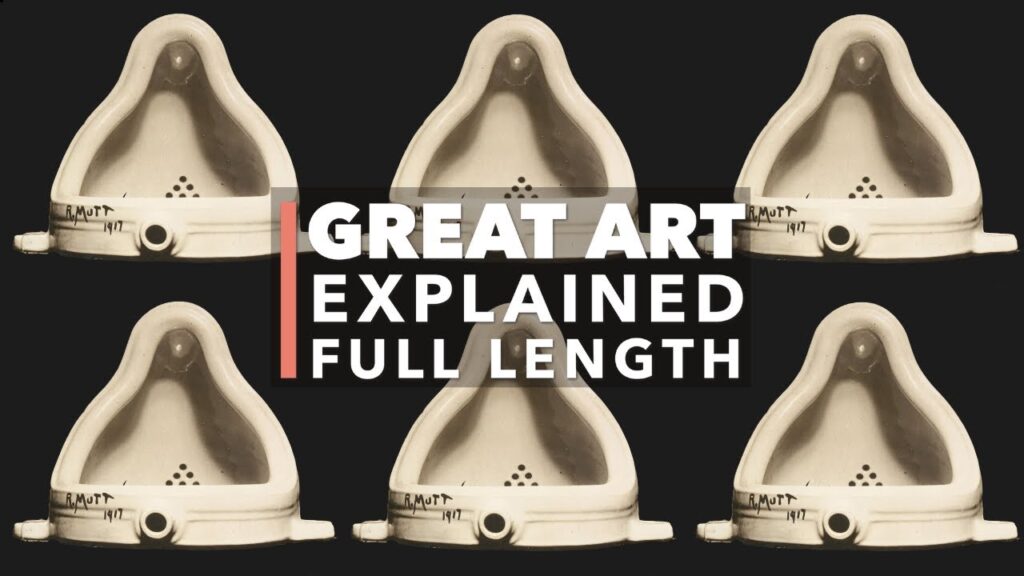

The famous urinal, entitled Fountain, would come later, in 1917, after he had relocated from Paris to New York. Technically, he didn’t sign his name on it at all, but rather “R. MUTT,” for Richard Mutt, a name partially “inspired by the comic strip Mutt and Jeff, which Duchamp loved. And Richard is French slang for a rich showoff, or a moneybags.” Submitted by a “female friend” and hidden behind a curtain at the show at which it made its debut, the original signed urinal would never be seen again. But it provoked a sufficiently enduring curiosity that, nearly half a century later, a market had emerged for carefully crafted sculptural replicas for Fountain and the other readymades. The irony could hardly have been lost on anyone with a sense of humor — or a willingness to question the nature of art itself — like Duchamp’s.

Related content:

What Made Marcel Duchamp’s Famous Urinal Art–and an Inventive Prank

Hear the Radical Musical Compositions of Marcel Duchamp (1912–1915)

Hear Marcel Duchamp Read “The Creative Act,” A Short Lecture on What Makes Great Art, Great

When Brian Eno & Other Artists Peed in Marcel Duchamp’s Famous Urinal

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.