For decades and decades, Warner Bros.’ Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies cartoons have served as a kind of default children’s entertainment. Originally conceived for theatrical exhibition in the nineteen-thirties, they were animated to a standard that held its own against the subsequent generations of television productions alongside which they would later be broadcast. Even their classical music-laden soundtracks seemed to signal higher aspirations. But when scrutinized closely enough, they turned out not to be as timeless and inoffensive as everyone had assumed. In fact, eleven Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies cartoons have been withheld from syndication since the nineteen-sixties due to their content.

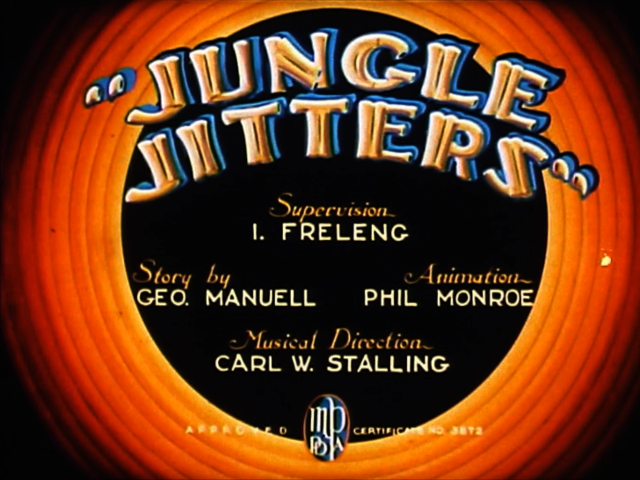

The LSuperSonicQ video above takes a look at the “Censored Eleven,” all of which have been suppressed for qualities like “exaggerated features, racist tones, and outdated references.” Produced between 1931 and 1944, these cartoons have been described as reflecting perceptions widely held by viewers at the time that have since become unacceptable. Take, for example, the black proto-Elmer Fudd in “All This and Rabbit Stew,” from 1941, a collection of “ethnic stereotypes including oversized clothing, a shuffle to his movement, and mumbling sentences.” In other productions, like “Jungle Jitters” and “The Isle of Pingo Pongo,” the offense is against native islanders, depicted therein as hard-partying cannibals.

At first glance, “Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs,” from 1943, may resemble a grotesque carnival of stereotypes. But as director Bob Clampett later explained, it originated when he “was approached in Hollywood by the cast of an all-black musical off-broadway production called Jump For Joy while they were doing some special performances in Los Angeles. They asked me why there weren’t any Warner’s cartoons with black characters and I didn’t have any good answer for that question. So we sat down together and came up with a parody of Disney’s Snow White, and ‘Coal Black’ was the result.” These performers provided the voices (credited, out of contractual obligation, to Mel Blanc), and Clampett paid tribute in the character designs to real jazz musicians he knew from Central Avenue.

However admirable the intentions of “Coal Black” — and however masterful its animation, which has come in for great praise from historians of the medium — it remains relegated to the banned-cartoons netherworld. Of course, this doesn’t mean you can’t see it today: like most of the “Censored Eleven,” it’s long been bootlegged, and it even underwent restoration for the first annual Turner Classic Movies Film Festival in 2010. Some of these controversial shorts appear on the Looney Tunes Gold Collection Volume: 3 DVDs, introduced by Whoopi Goldberg, who makes the sensible point that “removing these inexcusable images and jokes from this collection would be the same as saying they never existed.” Grown-ups may be okay with that, but kids — always the most discerning audience for Warner Bros. cartoons — know when they’re being lied to.

Related Content:

Donald Duck’s Bad Nazi Dream and Four Other Disney Propaganda Cartoons from World War II

Dr. Seuss Draws Anti-Japanese Cartoons During WWII, Then Atones with Horton Hears a Who!

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.